“We are in trouble”: Essential but undocumented farmworkers can't get aid

While millions of Americans will soon be benefitting from the $2 trillion coronavirus stimulus package, and the agriculture industry is expecting to receive up to $23.5 billion in aid from it, undocumented farmworkers like Jesús Zuniga won’t be receiving anything despite their essential role growing and harvesting crops sold in grocery stores across the U.S.

Originally from Hidalgo, Mexico, Zuniga is 45 and has been living in California and working in the state’s agriculture industry for 20 years. He has picked onions and tomatoes and is currently removing weeds from grape vineyards.

“We are in really trying times and we are in trouble as farmworkers,” Zuniga told CBS News in Spanish.”We are essential workers, we pay taxes, so we’d hope that [the government] would give us help just as they are planning to with others who have documentation,” he said.

Zuniga worries that if he were to contract the highly contagious virus he would have no way to support his children, who are still living in Mexico.

“I have a son who was in a motor accident, he has a broken arm that needs surgery. I’m terrified we won’t be able to work, and I won’t have any money to send to pay for the surgery. He is 20 years old and my other son is 19 years old. They rely on me.”

Teresa Romero, president of the United Farm Workers (UFW), said she and the union are continuing to fight for workers to see what the state and federal government can do.

“You know, the irony: They’re essential, but they do not have essential rights. And they’re the ones that are feeding us all,” she said.

UFW sent two open letters to agricultural employers in March, asking that they extend sick leave and arrange easy access to medical services to their non-union farmworkers.

“We need their employers to come to the table and figure out how we can as a team, help these farmworkers who are the backbone of the industry,” Romero said.

When UFW polled workers on March 27, 77% said that their non-union employers had not provided best practices or made changes in regard to COVID-19.

Elvira, who asked to only use her first name, is 27 and has been working in the fields growing mandarins and citrus fruit for four years. She said the company she works for has not “given us any information of instruction on how to take precaution, or changed anything in response to the pandemic,” has not provided masks and gloves, and still continues to hold morning meetings with everyone standing together.

“They haven’t told us anything about the virus at all,” Elvira said. “They aren’t taking us into consideration. They aren’t worried about us, they are only worried about making sure their production goes well.”

Elvira, a mother of four children ages 4-12, said she feels more pressure financially now that her kids are not in school. She is paying around $200 a week to leave them with a caretaker, whereas before she paid $60 a week just for her youngest.

“My kids are just as worried,” she said. “They see the news and they ask why we aren’t going into quarantine like the rest of them — and I have to explain that if I don’t work, then who will bring the necessary things home?”

Marta Acevedo is a 56-year-old union farmworker who lives in Santa Rosa, California. She works in the fields moving, growing and processing grapes for a vineyard. Although she is also concerned about contracting the virus, she feels that “the company is doing all that they can to help us.”

“The company gave us papers that explained what the virus is, how to protect ourselves, and how to act throughout this situation. They told us we should wash our hands, stay at least 6 feet apart, and eat inside of our cars if we preferred to.”

In the Salinas Valley, one company that is making substantial efforts to protect its 1,500 union farmworkers during the outbreak is the D’Arrigo Brothers company, which grows, packs and ships Andy Boy broccoli, cauliflower and other produce.

CEO John D’Arrigo told CBS News that the company now has “quite the inspection process.” When farmworkers arrive to work for the day, they must be scanned for fever, dry cough and other symptoms associated with coronavirus.

He said extreme sanitization measures are being taken, along with efforts to educate workers on correct protocols to make sure everything is clean. He said portable hand sanitizers have been installed all over, and equipment, transportation buses and bathroom facilities are being sanitized throughout the day.

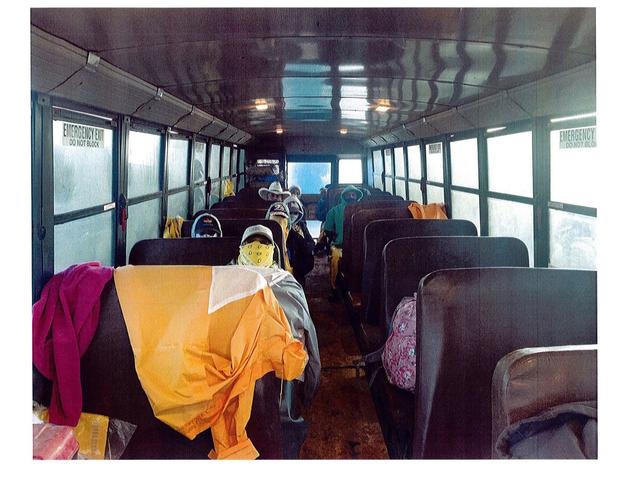

“We’re just trying to make sure the entire workforce, both here and when you go home, your whole family is safe,” D’Arrigo said. He added that the buses that are used to transport farmworkers to the field now require social distancing and assigned seats.

“Let’s say you’re a broccoli crew, and you’re Bus 34. Well, that’s your bus. And that seat on that bus is your seat now permanently,” he explained. “That’s a seat you get on, and that’s a seat you get off — and nobody gets in your seat. We want one person per seat, and now we want every other seat empty.“

According to Armando Elenes, secretary treasurer at UFW, the D’Arrigo Brothers company is the only one “stepping up in a big way” with such extensive food safety and coronavirus prevention measures.

But Jesús Zuniga and Elvira feel like their non-union employers have ignored the coronavirus pandemic altogether. They are terrified and hoping for change.

“We are upset because the company should have done something by now to inform us and help protect us,” said Zuniga.

Leave a Reply