New York City's Hart Island: An overlooked final resting place

On a deeply cold Saturday morning in January, correspondent Erin Moriarty took a nearly-empty ferry to a speck of land in Long Island Sound. For most souls who go there, it’s a one-way trip.

Hart Island is where the city of New York buries the unknown, the unclaimed, or those too poor to afford a burial. At 101 acres, it’s the largest Potter’s field in the country. [No cameras or cell phones are allowed.]

Moriarty went with Elaine Joseph, whose infant daughter, Tomika, is among the one million people buried there. “We’re going today because it is her birthday, and I’m commemorating her 42nd birthday,” Joseph said.

“There are no markers; there’s a mass grave. You just know there’s bodies buried there ’cause they told us so.”

“But you go?”

“I go. Because it’s all I have. It’s all I have left.”

In January 1978, Joseph was a 23-year-old nurse, pregnant and living with her boyfriend, when she unexpectedly went into labor and gave birth a month early. “It was my first child. And I was happy to be having her,” she said.

Days later, she said, her daughter needed emergency surgery for a heart deformity. New York City was in the middle of a crippling snow storm: “I couldn’t get to the hospital. There were no trains, there were no buses. There was no public transportation.”

She was home when she got the news: “They said she had another cardiac arrest and she died.”

“You had to hear that on the phone?” Moriarty asked.

“Yes, I couldn’t be there. That’s one of my main regrets, is that I was not there at the hospital with her.” Getting tearful, Joseph said, “Excuse me, it’s 41 years, but it never goes away.”

When she did get to the hospital to claim the body of her baby girl, “They said, ‘She was already buried.’ I’m like, ‘Buried how?’ They said that I signed to have her buried in the city cemetery.”

“Did anyone mention Hart Island to you at that point?”

“I had never heard of the term ‘Hart Island’ ever in my life,” said Joseph.

Until recently, most people had never heard of Hart Island, although it’s been a part of New York since 1868, when officials paid $75,000 (or more than a million dollars in today’s money) to make it a city cemetery.

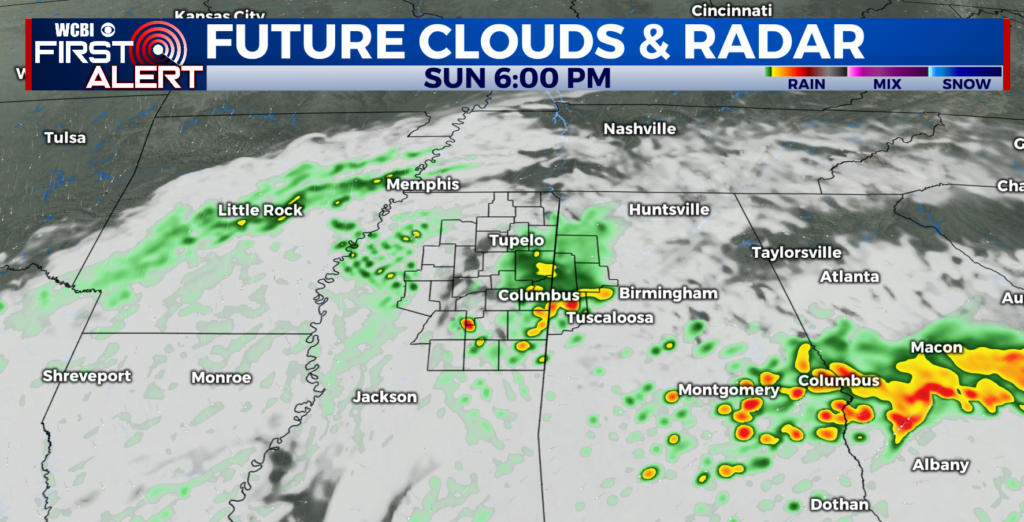

Hart Island might have remained out of view, if not for COVID-19, and the shocking aerial photos showing the devastation of a pandemic on those without resources.

In the last month, New York went from burying 25 bodies a week at Hart Island to five times as many.

“It’s always existed on the margins of the city,” said New York City Councilman Mark Levine. “And it’s been the place where we have buried those who were marginalized in life for generations.”

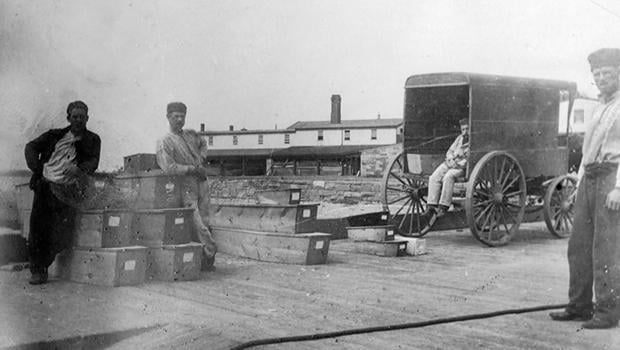

What makes Hart Island so unusual, said Levine, is that for much of its history, it’s been run by the Department of Correction, using inmate labor: “It’s almost out of a Dickens novel – that it’s inmates from Riker’s Island who are responsible for burials there.”

Victims of various pandemics – tuberculosis, the Spanish Flu, and AIDS – have been buried in secrecy, and sometimes in shame.

Until his release from jail in February, Vincent Mingalone placed pine boxes in mass graves on Hart Island. “I would take a wax crayon, write the name of the deceased, their last name in big letters on the side of the box,” he said.

“And what do you know about these people, other than their names and the day they died?” asked Moriarty.

“That’s pretty much all we know,” Mingalone replied. “But you always wondered: these are fellow New Yorkers. Is this somebody who served us coffee? Was this somebody who tailored our clothes, did our laundry?”

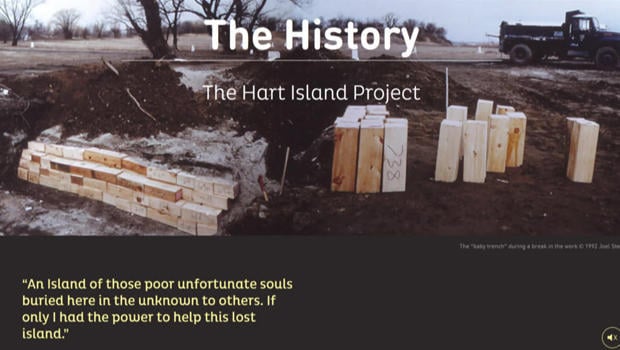

The city refused to release the names of those buried there, until Melinda Hunt, a visual artist, sued to obtain them.

“So, all of the sudden in 2008, I had 50,000 burial records,” Hunt said.

She created the Hart Island Project, an online memorial. “The whole point of a cemetery is storytelling,” she said. “The city had no reason to deny families this information . And there were so many families.”

And that’s how, in 2009, Elaine Joseph finally discovered where her infant daughter was buried, 31 years after she’d died.

“It’s not only my daughter that’s buried there; it’s all these others,” Joseph said. “Everybody belonged to somebody. Everybody had a mom, had a dad, had somebody. And many of them, families don’t even know they are there.”

Visitation to Hart Island is very limited. Joseph had to schedule this birthday celebration months in advance. She left a toy for her daughter, while a Corrections officer took Polaroids to mark the occasion.

Joseph said, “I could accept that she died. That I can accept. What I couldn’t accept is that I lost track of where her body went, and how she was treated after death.”

Councilman Levine said, “That final resting place has never been as dignified as it should have been. It’s never gotten the respect it needed. And that certainly needs to change.”

Last December, the New York City Council transferred control of Hart Island to the Parks Department. Earlier this month, inmates were replaced by paid landscape workers.

Many are hopeful that next year, Hart Island will be open as a memorial park, honoring those buried there.

Elaine Joseph said, “Everybody’s human. We’re all human. Maybe we don’t all have money, but we all deserve dignity.”

For more info:

Story produced by Mary Raffalli. Editor: Joe Frandino.

Leave a Reply