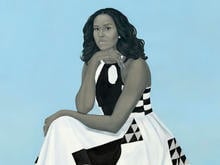

A portrait of artist Amy Sherald

Now on display in Washington: the official portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama. The story of the artist who painted the former first lady is the story Alex Wagner has to tell:

Last week, Amy Sherald went from being a virtual unknown to one of the most talked-about artists in the world.

On Monday her painting of Michelle Obama was unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery, alongside Kehinde Wiley’s portrait of President Barack Obama.

Portrait unveiling of former President Barack Obama and former First Lady Michelle Obama at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., Feb. 12, 2018.

Photo by Pete Souza

Pete Souza

Both Sherald and Wiley were interviewed and chosen for the job by the Obamas themselves.

As the former first lady said Monday, “She came in and she looked at Barack and she said, ;Well, Mr. President, I’m really excited to be here and I know I’m being considered for both portraits, but Mrs. Obama ..’ — she physically turned to me, and she said, ‘I’m really hoping that you and I can work together.'”

Wagner asked Sherald, “You maybe had a particular interest in painting her?”

“Yeah!” she laughed. “I mean, [Mr. Obama] was asking questions as well. And she was like, ‘Shhh, no, no, no, no, no.'”

Unlike Wiley, President Obama’s portraitist, Amy Sherald, age 44, had been largely unknown. After having waited tables and taken out loans, this was her big break.

Wagner asked, “Tell us how game-changing this moment is.”

“I am relieved that I can pay back my school loans,” Sherald said. “Becoming an artist is not empirical; it’s not about hard work. You have to put the work in, but that doesn’t mean you’re going to make it. I think, hustling for that long, it kind of, like, chips away at your self-esteem. And then, the breakthrough comes, and you’re like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s who I am. Like, this is who I am!'”

The portrait is similar to Sherald’s other works, except her models — exclusively black and never smiling — are usually strangers she meets on the street, not former first ladies.

She described her process of working with Michelle Obama: “We had two sittings. But you’re still always a little bit nervous, having to look her in her eyes, ’cause I have to study the face before I photograph to try to figure out what I want, and those little intense moments where you just have to have courage to keep looking, because you get bashful because, you know, you’re looking at the first lady!”

Why does she paint black skin in grayscale? “It just looked good, the gray skin on these bright colors,” she said. “I think, also, I was subconsciously struggling with not wanting to be marginalized.

Amy Sherald’s portrait of first lady Michelle Obama (2018).

Amy Sherald/National Portrait Gallery

“And I say that because I feel like the black body is a political statement in itself, right? So, on canvas all of a sudden I’m making a political statement just because I’m painting brown skin. But, I paint the way that I paint. And she chose me, she knew what to expect.”

“There are some people who look at the portrait of the first lady, and they say, ‘I don’t see her in it. I don’t see the Michelle Obama that I know.”

Sherald said, “Everybody is invested in [the Obamas] in all kinds of ways, on all different levels. And so, for me to even want to paint her makes me crazy. Because I’m setting myself up for criticism, right? I feel like I captured her. When I look at it, I see her; I see the Michelle that was present at the sitting, you know, a contemplative, graceful woman who understands her place in history.”

Amy Sherald photographs a subject at her Baltimore studio.

CBS News

Today, Amy Sherald has a place in history. Her paintings — which she works on in her Baltimore studio — are now selling for up to $50,000 each.

But while this is her moment, it’s a moment she wasn’t sure she would live to see.

When she was 30 she learned her heart was failing: “I had been walking around with my heart function at 18%, which is what most people get transplanted at. But I was asymptomatic, no symptoms at all.”

Plus, there were relatives back home who needed her help. So, she put aside her brushes and returned to Georgia. At one point, Sherald stopped painting for four years.

In 2012, her brother died of cancer. Just days later, she received a heart transplant, from a young donor, nearly a decade after her diagnosis.

“My brother dying changed me,” she said. “I didn’t realize how strong I was until I lost my brother. And then I realized what my strength [is]: I can get through stuff. And losing him only made me want to live my life even harder.”

For an artist who is all too familiar with mortality, Sherald seems to have found a sense of permanence. After all, her work now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.

“I think it matters that these portraits are so different,” she said, “because something happened in history that wasn’t supposed to happen. You know, there’s a continuum, and then, there’s a stop. And all of a sudden, you’re like, ‘What was this?’ So, 300 years from now, when the story’s been watered down — you know what I mean? — those portraits will speak to that moment with the intensity that is necessary to bring forth the truth of what happened and why they were here.”

For more info:

Leave a Reply