50 years later, Apollo 11 remains a defining moment

Watch coverage of the Apollo 11 50th anniversary Tuesday on “CBS This Morning,””CBS Evening News with Norah O’Donnell,” and streaming on CBSN. A CBS News prime-time special, “Man on the Moon,” airs Tuesday night at 10/9c.

In a culture steeped in high technology, from wearable computers to the internet of things and rockets that fly themselves back to pinpoint touchdowns, the Apollo 11 moon landing and Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind” are slowly fading from memory, a forever remarkable but increasingly distant bit of history.

After all, for anyone born after July 20, 1969, the day Armstrong set foot on the surface of the moon, there has never been a time when humanity was bound to Earth alone. For many, the stories of Apollo 11, five subsequent moon landings and the near disaster of Apollo 13 are remembered from history class, not from personal experience.

But for an older generation, the sons and daughters of the “Greatest Generation” who designed, built, launched and flew the Apollo missions, the first moon landing will forever stand out as a seminal event in human history, a gripping life-or-death drama played out on live television 240,000 miles from Earth.

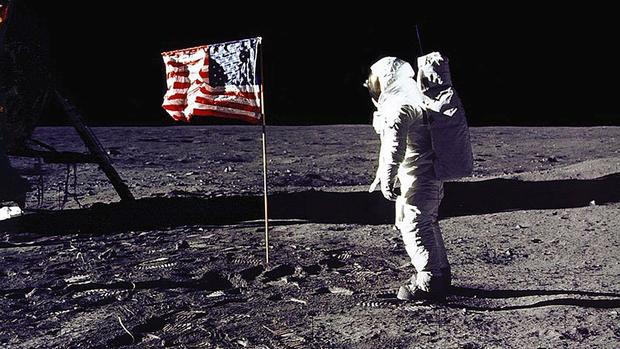

On the 50th anniversary of the first moon landing, virtually anyone watching television or listening to the radio that day can recall where they were at 4:17:40 p.m. EDT when Armstrong and lunar module pilot Buzz Aldrin, leaving crewmate Michael Collins behind in orbit, swooped to a nail-biting touchdown on the Sea of Tranquility.

With only a few seconds of fuel remaining, after disconcerting computer program alarms and a navigation glitch that forced Armstrong to take over manual control to avoid a boulder-strewn landing site, the four-legged spacecraft settled to the surface in clouds of fast-dissipating moon dust.

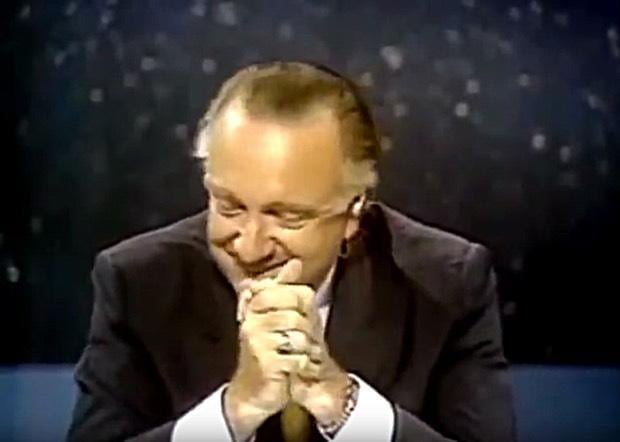

“Man on the moon!” CBS News anchor Walter Cronkite emotionally exclaimed, listening along with millions around the world as Armstrong and Aldrin worked through their engine shutdown checklist. “We copy you down, Eagle,” astronaut Charlie Duke called from mission control in Houston as if seeking confirmation.

“Houston, Tranquillity Base here,” Armstrong famously replied. “The Eagle has landed.”

“Roger, Twan… Tranquillity, we copy you on the ground,” Duke stammered in return. “You’ve got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We’re breathing again. Thanks a lot.”

They weren’t the only ones. Cronkite, a long-time space enthusiast, was virtually speechless. “Oh, boy!” he exhaled in relief, taking off his glasses and rubbing his hands together with pent-up emotion.

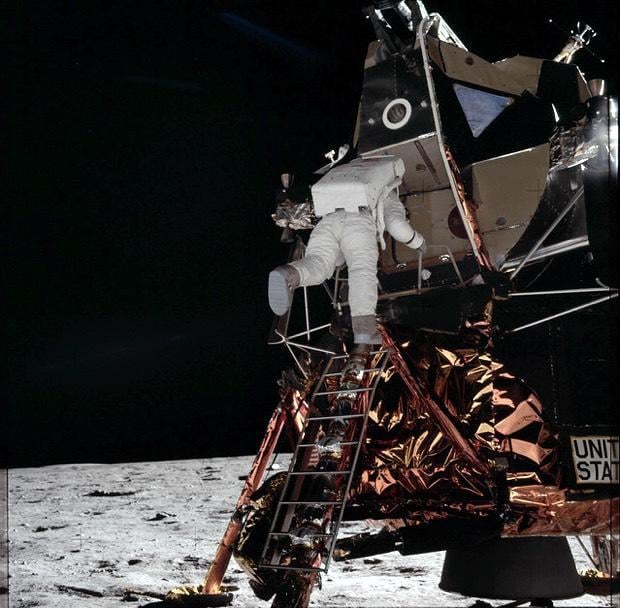

Six-and-a-half hours later, with one of the largest global television audiences in history looking on, Armstrong stood poised on the lander’s foot pad before stepping onto the lunar surface, clearly visible in a grainy black-and-white image.

“Boy, look at those pictures! Wow!” Cronkite marveled. “Armstrong is on the moon, Neil Armstrong, 38-year-old American, standing on the surface of the moon on this July 20th, nineteen hundred and sixty nine.”

An instant later, at 10:56 p.m., Armstrong stepped off the footpad and onto the the finely-powdered surface.

“That’s one small step for (a) man, one giant leap for mankind.”

Whether he inadvertently dropped the “a” or simply misspoke in the thrill of the moment, Armstrong’s words briefly united the people of planet Earth with shared pride for an achievement dreamed of since humans first looked up at the sky in wonder.

“For one priceless moment in the whole history of man, all the people on this Earth are truly one,” President Richard Nixon radioed the moonwalkers from the Oval Office. “One in their pride in what you have done, and one in our prayers that you will return safely to Earth.”

John Noble Wilford, leading The New York Times’ coverage, started with just eight words: “Men have landed and walked on the moon.” No embellishment was needed.

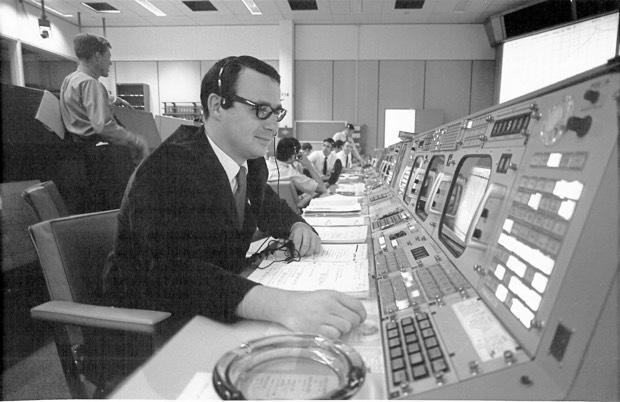

For many in mission control that day, the emotional impact of the landing and moonwalk did not immediately hit home. For flight controller Ed Fendell, it sank in the next day during breakfast at a Dutch Kettle restaurant near the Houston space center.

“Two guys walked in and sat down next to me,” he recalled in an interview. “They were out of the gas station down on the corner, dirty nails, grease on their clothes. And they started talking and I couldn’t help but hear them. One says, ‘You know, I landed on D-Day in World War II,’ and he said, ‘I never felt prouder to be an American than I did yesterday.’

“All of a sudden, it hit me with a realization of what we had done. … I threw my money down on the counter, went out to my car and started crying.”

“A new stage for mankind”

One can debate the historical significance of the moon landing, but in 500 years, the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr. wrote in 1999, when “Pearl Harbor will be as remote as the War of the Roses,” the Apollo 11 moon landing may well be remembered as the most significant event of the 20th century. And that includes two world wars, the development of Einstein’s theory of relativity, quantum physics and nuclear weapons.

Glynn Lunney, the flight director on duty for Apollo 11’s climb back to lunar orbit, agreed, saying “for all the millennia that humans have walked on this planet and looked up at the moon and looked up at the stars, this was the first time when two of us walked and worked and lived on another planet.

“And in the big sweep of history yet to come, we may look back on this not as a technological achievement, we may end up looking back and seeing that it was the beginning of a new stage for mankind as we know it.”

Now 82, Lunney said when he looks up at the moon today, “I think of all the people who worked on (Apollo) and how well they performed. I mean, they were doing something that five years earlier was the impossible, right? And they just said, yeah, it’s impossible. But we’re gonna do it anyway.”

Fifty years after the fact, Apollo 11’s story is long complete, a success so towering it has worked its way into everyday vernacular as an achievement against which daily frustrations are measured. Who hasn’t heard someone ask, “If they can put a man on the moon, why can’t they (fill in the blank)?”

“I think (young) people get it” Lunney said in June. “They didn’t participate in it. They didn’t know all the technical stuff and the whiz-bang stuff. But they know we did something really, really big. Nobody else had done it before, and nobody else has done it since. And it took a lot of courage.”

Ten more American men would follow Armstrong and Aldrin onto the moon’s stark surface, eventually roving about in high-tech dune buggies equipped with color TV cameras, bringing home a priceless collection of rocks and soil — 842 pounds total — that is still helping scientists decipher the history of the solar system.

But barring the dramatic Apollo 13 rescue in 1970, the moon program never again captured the world’s attention to such a degree or garnered the political support needed for equally ambitious programs in its wake. By September 1970, three moon landings had been canceled.

“We didn’t think it could be done”

The flight of Apollo 11, then, symbolized an end and a beginning. It was the beginning of humanity’s first steps away from the home world, but it marked the end of a nation’s willingness to provide unlimited support for the very exploration that came to symbolize its technological leadership on the world stage.

That visionary leadership is precisely what President John F. Kennedy gave the United States on May 25, 1961, when he told a joint session of Congress: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

In the month preceding that speech, on April 12, 1961, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human in space, completing one orbit around the planet in a Soviet triumph that shocked the American public, the media and lawmakers in Washington. Five days later, the CIA-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba began, ending three days later in a humiliating defeat at the hands of Fidel Castro’s Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.

Less than three weeks after that, as Kennedy was struggling to find a way forward for the United States after what were widely perceived as unacceptable setbacks, NASA launched Mercury 7 astronaut Alan Shepard on a brief 15-minute sub-orbital space flight. It was a poor second to Gagarin’s orbital flight, but the nation was thrilled, at least some of its confidence restored.

Kennedy was listening. Twenty days later, on May 25, the president set a trip to the moon, before the decade was out, as the nation’s objective in space. It was a master stroke, an audacious, yet easy-to-understand goal that instantly captured the nation’s imagination.

“We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard,” the president said on Sept. 12 during a speech at Rice University. “Because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win.”

Lunney and many others in the nation’s infant space program were stunned by the unexpected directive.

“When we were having a beer talking about that, we didn’t think it could be done,” Lunney recalled with a smile. “We were working on Mercury at the time. Mercury was a 2,000-pound ship. And what we had to deal with was getting 200,000 pounds in Earth orbit (just) to get started.

“It was a stunning thing,” he went on. “It was a wonderful thing to see how well the Americans did pooling together our resources and our talents. And inventing a whole new world of space operations.”

Gene Kranz, the legendary flight director who managed Apollo 11’s descent to the lunar surface, said Kennedy’s vision “established the direction for the nation to get moving. And the nation started moving.”

“The environmental movement was starting at that time, the Peace Corps was starting at that time, the civil rights movement was starting,” Kranz said in an interview, sitting at his console in the recently restored Apollo 11 mission control room at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

“This was the start of not only the space revolution, but the technology revolution within our nation,” he said. Looking across the iconic consoles and screens that once displayed the second-by-second heartbeat of Apollo 11, he added: “This is where it all began.”

Long and difficult road to the moon

The road to the moon would be difficult, hugely expensive and in a few cases, marred by tragedy. Three astronauts — Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Roger Chaffee and Ed White — were killed Jan. 27, 1967, when a flash fire erupted and swept through their problem-plagued Apollo 1 command module during a launch pad test at Cape Canaveral.

Five other astronauts — Theodore Freeman, Charles Bassett, Elliot See, Edward Givens and Clifton “C.C.” Williams — were killed in aircraft crashes or car wrecks before getting a chance to fly in space.

The United States would eventually spend $25 billion — $288 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars — developing the technology to send 12 astronauts to the surface of the moon and to bring back 842 pounds of lunar soil and rocks. The bulk of those samples are carefully maintained at the Johnson Space Center.

While science was never the primary justification for Apollo, it remains, perhaps, its most enduring legacy.

“There is not a price tag on this collection,” said geologist Ryan Zeigler, NASA Apollo sample curator, during a CBS News tour of the laboratory where the rocks are stored. “And nor will we ever put a price tag on the collection. They’re truly priceless. That word gets thrown around a lot, but no amount of money would let me buy new Apollo samples.”

Andrew Chaikin, author of “Man on the Moon” and an authority on the Apollo program, adds another enduring legacy: “the perspective, the change in awareness, looking back at the Earth from the moon and seeing it as a planet and in the words of (astronaut) Jim Lovell, a ‘grand oasis in space.'”

“So many of the guys talk about the seeming fragility of Earth, that we live on a world that we need to protect and cherish,” he said. “We had pictures of the Earth from the moon from the robotic missions, but there’s nothing like having a person come back and talk about that experience.””

The moon program got off the ground with the successful launch of Apollo 7 on Oct. 11, 1968, a shakedown cruise for the redesigned post-fire Apollo command module in low-Earth orbit. NASA originally planned to follow that flight with an Earth-orbit test of the command and lunar modules.

But the lander was behind schedule and in a bold step — some NASA insiders consider it the boldest decision of the Apollo program — program manager George Low suggested sending the Apollo 8 capsule, carrying astronauts Frank Borman, William Anders and Lovell, on a flight to orbit the moon, the first piloted launch atop a Saturn 5 rocket.

Launched Dec. 21, 1968, the mission was a resounding success. In a live television broadcast from lunar orbit that Christmas Eve, the astronauts took turns reading the first several verses of Genesis, a moving moment that provided a hint of the drama to come.

Time magazine named the Apollo 8 crew members “Men of the Year” for 1968, the same year Martin Luther King was assassinated and Richard Nixon was elected president. The dizzying pace of the Apollo program was enough to make Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 vision of the future — “2001: A Space Odyssey” — with its commercial flights to orbit, giant space stations and moon bases, utterly believable.

NASA followed the Apollo 8 mission with a test of the strange-looking lunar lander in Earth orbit during the flight of Apollo 9 and then in orbit around the moon during Apollo 10, a dress rehearsal that tested all the maneuvers and procedures needed for a moon landing except the final descent to the surface.

The stage was finally set for Apollo 11.

A voyage into history

More than a million spectators gathered along area highways, waterways and beaches to take in the historic launch. More than 3,000 journalists looked on from a press site 3.2 miles from launch complex 39A where Apollo 11’s mammoth, 36-story-tall Saturn 5 rocket stood steaming in the morning sun as supercold liquid oxygen boiled off and was vented overboard.

At 9:32 a.m., the rocket’s five huge F1 engines roared to life, generating 7.5 million pounds of thrust as they gulped a staggering 15 tons of fuel per second. Ever so slowly, the gigantic Saturn 5, still the most powerful rocket ever flown, majestically climbed skyward, the deafening roar of its engines overwhelming shocked spectators when it finally reached them.

“We are off! And do we know it, not just because the world is yelling ‘lift-off’ in our ears, but because the seats of our pants tell us so!” Collins wrote in his memoir “Carrying the Fire.” “Shake, rattle and roll! Noise, yes, lots of it, but mostly motion as we are thrown left and right against our straps in spasmodic little jerks. It is steering like crazy.”

Twelve minutes later, the third stage, carrying the command module Columbia and the lunar lander Eagle, was safely in orbit. After double checking the health of the spacecraft, the crew re-started the single hydrogen-fueled third stage engine at 12:22 p.m., blasting the crew out of Earth orbit and on toward the moon at an initial velocity of seven miles per second.

An hour and a half later, Columbia separated from the third stage and the lunar lander. Collins took manual control, flipped Columbia 180 degrees, docked with the lander and pulled it free of the no-longer-needed third stage.

Three days later, the astronauts flew behind the moon and out of contact with mission control in Houston. Flying backward, the main engine in Columbia’s service module ignited at 1:21 p.m. on July 19, burning for five minutes and 57 seconds to slow the ship down enough to into orbit.

Armstrong wasted no time looking at the cratered surface below and comparing it to photos captured earlier by the crews of Apollo 8 and 10.

“Apollo 11 is getting its first view of the landing approach,” Armstrong radioed. “It looks very much like the pictures, but like the difference between watching a real football game and watching it on TV. There’s no substitute for actually being here.”

The next day, slipping behind the moon during their 12th lunar orbit, Armstrong and Aldrin undocked Eagle from Columbia for the historic descent to the surface.

“The Eagle has wings!” Armstrong said.

A few minutes later, Collins, alone aboard the command module, said farewell to his crewmates: “OK, Eagle … you guys take care.”

“See you later,” Armstrong replied. The stage was set for the most dramatic moments in the history of the space program.

The pressure was almost unbearable in mission control.

“You’d have had to be an idiot not to understand that this was the time we were going to try to land on the moon,” guidance officer Stephen Bales told the author in an earlier interview. “I was just scared to death, mortified. I was really glad I could talk. I was that scared.”

Despite initially poor communications, Kranz gave the crew a “go” for powered descent initiation, or PDI. Right on time, at 4:05 p.m., the lander’s engine fired up at an altitude of 50,000 feet. From there to the surface — the finish line in the Cold War space race — would take just 12 minutes.

Flying backwards as the descent engine fired, Armstrong and Aldrin initially were oriented feet first and face down toward the moon’s surface so they could visually monitor their trajectory. Armstrong realized Eagle would be “landing long,” that is, somewhat beyond the center of the planned landing zone.

The lander then rotated around its long axis, putting the astronauts face up toward deep space so its landing radar could “see” the surface of the moon. And as soon as the radar locked on, Bales saw Eagle was descending 25 feet per second faster than expected. If the descent rate increased to 35 feet per second, the crew would have to abort and make an emergency climb back to orbit.

But as the seconds ticked by, the rate did not increase. It was clear by now that Eagle would be landing long, but there were no signs of any other guidance problems and Bales decided the crew’s flight computer was behaving within acceptable limits.

Then, five minutes and 17 seconds into the 12-minute descent, an alarm suddenly blared in the cockpit and the crew saw a green alarm code — 1202 — flash on their guidance computer display.

“Program alarm,” Armstrong called out. “It’s a 1202.”

Seconds ticked by.

“Give us a reading on that 1202 program alarm,” Armstrong repeated.

Eleven days before launch, Kranz and the White Team, along with two astronauts standing in for Armstrong and Aldrin, went through a final landing simulation. In a remarkable stroke of either pure luck or prescient planning, the simulation engineers decided to throw a very similar program alarm into the practice run.

Bales, 26, and Jack Garman, a 24-year-old computer whiz in a nearby support room scrambled to come up with an explanation. Believing the computer was malfunctioning, Bales called for an abort.

As it turned out, the alarm simply meant the computer was overloaded, unable to complete all the required computations in a given cycle. As programmed, it was prioritizing its tasks and getting the most important calculations done before starting a new cycle. Bottom line? Bales should have allowed the landing to continue.

When Armstrong called down the 1202 alarm during the actual descent to the moon, Bales and Garman were ready. After verification from Garman, Bales told Kranz, “We’re go on that alarm.” More alarms cropped up as the descent continued, but Bales and Garman were increasingly confident they could be safely ignored.

Nearing the surface, Armstrong saw the flight computer’s trajectory was carrying them toward a large crater and a field of boulders. Taking over manual control, he began flying Eagle like a helicopter, slowing the descent while continuing to fly downrange in search of a smoother landing site.

“Our auto-pilot was taking us into an area that wasn’t a good area to land,” Armstrong told “60 Minutes” correspondent Ed Bradley. “It was a very large crater, about the size of a big football stadium with steep slopes covered with very large rocks about the size of automobiles. That was not the kind of place I wanted to try to make the first landing.”

The unplanned maneuvering and extended flight time meant Eagle was burning up much more fuel than expected. Nearing the surface, the crew was in a race against the clock.

“Sixty seconds,” Duke called out from Houston, telling Armstrong and Aldrin that Eagle had an estimated one minute’s worth of usable propellant left in the tank.

“We know we have two minutes, 120 seconds, of fuel at a 30% throttle setting,” Kranz said. “We know they’re landing long. … But Neil Armstrong is now the guy in charge. And he is flying that spacecraft around, trying to find the place.”

Aldrin was too busy to acknowledge the 60-second call. He was providing a running commentary for Armstrong, giving him Eagle’s altitude, horizontal velocity and descent rate in feet per second.

“Down two and a half (feet per second). Forward. Forward. Good. 40 feet, down two and a half. Kicking up some dust. 30 feet, two and a half down. Faint shadow. Four forward. Four forward. Drifting to the right a little. OK. Down a half.”

“I’m starting to get sorta uptight,” Kranz recalled. “And pretty soon, it’s 30 seconds (of fuel remaining). And now I’m starting to really sweat it out.”

Then, just when Kranz was expecting to hear the 15-second warning, Armstrong set the lander down and shut down the engine.

“Houston, Tranquility Base here,” Armstrong said. “The Eagle has landed.”

Armstrong and Aldrin spent 21 hours and 36 minutes on the moon — two hours, 31 minutes and 40 seconds walking about its surface — before blasting off and rejoining Collins aboard Columbia. The astronauts splashed down in the Pacific Ocean four days later, on July 24. They never flew in space again.

Collins, author of what many consider the best book ever written by an astronaut — “Carrying the Fire” — and Aldrin, a still-vocal space activist and proponent of human flights to Mars, would both participate in 50th anniversary celebrations, but without their crewmate. Armstrong, the famously reticent “First Man,” died on Aug. 25, 2012, at age 82, after complications following heart surgery.

Planning a return to the moon

Fifty years after Apollo 11’s voyage into history, NASA is preparing to return astronauts to the surface of the moon by the end of 2024, using a huge new rocket called the Space Launch System, or SLS, and Orion capsules described as “Apollo on steroids.” They will dock with a mini space station in lunar orbit and descend to the surface in a commercially-built lander.

The program is known as Artemis, the sister of Apollo and goddess of the moon in Greek mythology. The 2024 target date, imposed by the Trump administration, may or may not be doable depending on whether Congress agrees to the increased spending required to turn the plan into reality.

Chaikin warns that despite 50 years of progress on the high frontier a return to the moon will not be easy despite having done it before. In an interview, he recalled a conversation with Max Faget, the brilliant engineer who designed the Mercury capsule and played a major role in the Gemini and Apollo programs.

Faget and Bob Gilruth, the first director of what is now the Johnson Space Center, were walking along a beach near Galveston, Texas, Chaikin said, and “there was a big moon up in the sky and they stood there looking at it.” Gilruth then said to Faget, “Max, someday people are going to try and go back to the moon. And they’re going to find out how hard it really is.”

Leave a Reply